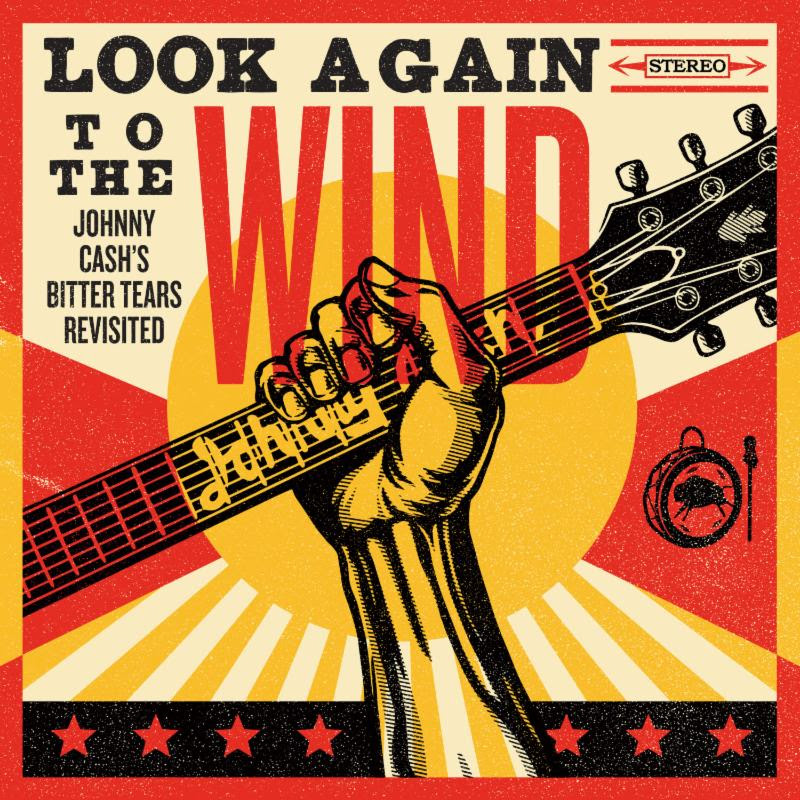

To celebrate the 50th Anniversary of one of Johnny Cash’s most personal releases, “Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian,” Sony Music Masterworks will commemorate the occasion with “Johnny Cash’s Bitter Tears Revisited” ( August 19.) Produced by Joe Henry and featuring country and Americana music giants Kris Kristofferson, Emmylou Harris, Steve Earle, Bill Miller, Gillian Welch and David Rawlings, and Norman and Nancy Blake, as well as up-and-comers the Milk Carton Kids and Rhiannon Giddens. Each artist interpreting the music for a new generation. As his project was for Cash, the new collection “is a labor of love with a strong sense of purpose fueling its creation.”

Of all the dozens of albums released by Johnny Cash during his nearly half-century career, 1964’s Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian was among the closest to the artist’s heart. A concept album focusing on the mistreatment and marginalization of the Native American people throughout the history of the United States, its eight songs-among them “The Ballad of Ira Hayes,” a #3 hit single for Cash on the Billboard country chart-spoke in frank and poetic language of the hardships and intolerance they endured.

“Prior to Bitter Tears, the conversation about Native American rights had not really been had,” says Henry, “and at a very significant moment in his trajectory, Johnny Cash was willing to draw a line and insist that this be considered a human rights issue, alongside the civil rights issue that was coming to fruition in 1964. But he also felt that the record had never been heard, so there’s a real sense that we’re being asked to carry it forward.”

Bitter Tears, widely acknowledged for decades as one of Cash’s greatest artistic achievements, did not realize its stature as a landmark recording easily and quickly. At the time that Cash proposed the album, he was met with a great deal of resistance from his record label. They felt that a song cycle revolving around the Native American struggle as perpetrated by the white man took him too far afield of the country mainstream and Cash’s core audience. Cash still released the album and although it did not perform as well as he had hoped, he remained extremely proud of the album throughout his life.

Ironically, at the same time that his own label was balking because it felt he would alienate the country audience with his Native American tales, Cash was finding a new set of admirers among the burgeoning folk music crowd that had recently made stars of Bob Dylan, Joan Baez and Peter, Paul and Mary. Cash’s debut performance of “Ira Hayes” at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival had earned him rave reviews. His appeal was undeniably expanding beyond the country audience, and for those who did connect with Bitter Tears, among them a 17-year-old aspiring singer-songwriter named Emmylou Harris, its music was revelatory and important. “The record was a seminal work for her as a teenager,” says Henry. “She bought the album brand new and realized at that moment that Johnny Cash was a folk singer, not a country singer, and was involving himself politically and socially in a way that she had identified with the great folk singers at that moment.”

Henry’s awareness of Harris’ affection for Bitter Tears led him to invite her to contribute to Look Again To The Wind: Johnny Cash’s Bitter Tears Revisited. Following the epic, nine-minute album-opener “As Long as the Grass Shall Grow,” written by Peter La Farge-a folk singer-songwriter with Native American bloodlines who Cash had befriended-and sung here by Welch and Rawlings, Harris takes the lead vocal on the Cash-penned “Apache Tears,” which also features sweet, close harmonies by the Milk Carton Kids, the duo comprising Kenneth Pattengale and Joey Ryan. For Henry, carefully matching artist to song was integral to the integrity of Look Again To The Wind. For some of the tracks, that process required a great deal of consideration. But when it came to deciding who would interpret “The Ballad of Ira Hayes,” Henry quickly zeroed in on Kristofferson.

Another of five songs on the original album written by La Farge, “The Ballad of Ira Hayes” is based on the true story of Ira Hamilton Hayes, a Pima Indian who was one of the six Marines seen raising the flag at Iwo Jima in an iconic World War II photograph. Hayes’ moment of glory was followed upon his return to civilian life with prejudice and alcoholism-Cash, moved by Hayes’ story and La Farge’s recounting of it, vowed to record the song. When planning out Look Again To The Wind, Henry knew that only a few living singers could deliver the song the way he wanted to hear it. He called Kristofferson, utilizing Rawlings and Welch to sing background.

“I wanted somebody whose relationship with Johnny Cash was not only musical but personal,” he says. “I’d worked with Kris on a couple of other things and I thought why not ask? Who else has a voice with that kind of power and authority?” That same sense of intuition guided Henry to choose the other participants and the material they would render. For La Farge’s “Custer,” the album’s third song, the producer knew instinctively that Steve Earle was the right man for the job. “Steve is an upstart, and there are very few people I can imagine working right now who could deliver a song that is that pointed in that particular way and do it authentically without cowering from it or making it feel a little too arch,” Henry says. “He really could embody the kind of swagger that that song insists upon.”

Similarly, Henry chose Nancy Blake (with Harris and Welch on backing vocals) for the Cash-written “The Talking Leaves,” Norman Blake to sing “Drums,” the Milk Carton Kids to lead “White Girl” (both of those authored by La Farge) and the powerhouse vocalist Rhiannon Giddens of the Carolina Chocolate Drops for the original album’s finale, “The Vanishing Race,” written by Cash’s good friend Johnny Horton. To bolster the album (the original, typical of mid-’60s vinyl LPs, ran just over a half hour), Henry fills out the track list of Look Again To The Wind with reprises of “Apache Tears” and “As Long As the Grass Shall Grow”-both sung by Welch and Rawlings-and ends the set with the title track, a La Farge tune that did not appear on the original Johnny Cash album but instead on the songwriter’s own 1963 release As Long as the Grass Shall Grow: Peter La Farge Sings Of The Indians. Here it’s sung by Bill Miller, with Sam Bush providing mandolin and Dennis Crouch upright bass, a fine and fitting coda to the collection.

From the start, Henry looked at the project as one that would require great personal commitment and responsibility on his own part. Approached as potential producer of the project by the man who first envisioned it, Sony Music Masterworks’ Senior Vice President Chuck Mitchell (who’d been in conversations with Antonino D’Ambrosio, author of A Heartbeat and a Guitar,a book about the making of Bitter Tears), Henry immediately understood the importance of the assignment. “Johnny Cash was my first musical hero and I feel a profound debt to him as an artist, and as a courageous one,” he says. “How could I say no to that?”

He also realized that the Bitter Tears album held a special place in Cash’s canon, and that in many ways the issues it raised still resonate today-this had to be apparent in the new versions. “Mr. Cash knew that if he took this on, even if his point of view was not adopted, he had the power to be heard,” Henry says.

The album was recorded in three sessions: the first two in Los Angeles and Nashville and, lastly, one at the Cash Cabin, in Cash’s hometown of Hendersonville, Tennessee, where Bill Miller cut his contribution. Providing the instrumental backing for most of the album are Greg Leisz (steel guitar, guitars), Keefus Ciancia (keyboards), Patrick Warren (keyboards for the L.A. sessions), Jay Bellerose (drums) and Dave Piltch (bass).

TRACKLIST:

As Long as the Grass Shall Grow – Gillian Welch & David Rawlings

Apache Tears – Emmylou Harris w/The Milk Carton Kids

Custer – Steve Earle w/The Milk Carton Kids

The Talking Leaves – Nancy Blake w/ Emmylou Harris, Gillian Welch & Dave Rawlings

The Ballad of Ira Hayes – Kris Kristofferson w/ Gillian Welch & David Rawlings

Drums – Norman Blake w/ Nancy Blake, Emmylou Harris, Gillian Welch & David Rawlings

Apache Tears (Reprise) – Gillian Welch & Dave Rawlings

White Girl – The Milk Carton Kids

The Vanishing Race – Rhiannon Giddens

As Long as the Grass Shall Grow (Reprise) – Nancy Blake, Gillian Welch & Dave Rawlings

Look Again to The Wind – Bill Miller